The

Biblical mention of Joseph serving time in a prison is

noteworthy in itself. To us in the 20th century, serving time in

a prison as punishment for a crime seems quite natural. But in

the ancient world, this was not the case. The death penalty, a

fine, or even bodily mutilation were the usual means of making

people suffer for their crimes in the ancient Near East.

Prisons were rare in the ancient world. To see this, one need

only look at the Old Testament Law. There is nothing there about

serving a prison sentence for any sin or crime, and in fact

there is nothing Biblically or archaeologically that would lead

us to believe that the Hebrews even had prisons as we know them.

The importance, then, of the prison sentence of Joseph is that

the author of the book of Genesis is recording correct

information, for Egypt was one of the few nations in the ancient

Near East that had prisons in the classical sense of the term.

We

are very fortunate to have an Egyptian papyrus, translated and

published by the Egyptologist W. C. Hayes, that deals at length

with Egyptian prisons (Hayes 1972). We have mentioned it also

deals with Asiatic slaves in Middle Kingdom Egypt. Let us look

at what this papyrus tells us about prisons and prison life in

Egypt in the days of Joseph (Hayes 1972:37–42).

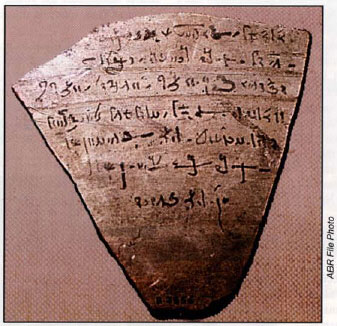

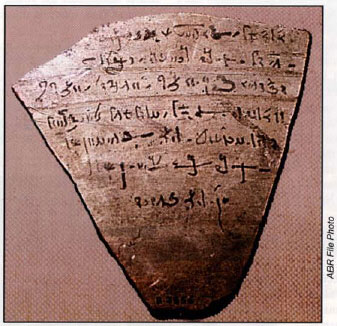

Ostracon (pottery sherd with writing) from the Chief Baker of

the Temple of Amun at Thebes acknowledging the receipt of wheat.

The

main prison of Egypt was called the “Place of Confinement.” It

was divided into two parts: a “cell-block” like a modern prison,

and “a barracks” for holding a large number of prisoners who

were forced into serving as laborers for the government. What

kinds of sentences were given to prisoners? We know little about

specific sentencing procedures. It does not seem that criminals

were given a number of years to serve in prison. Perhaps all

sentences were life sentences. In any case, some of the

prisoners in the Place of Confinement were “serving time” for

their crimes, as Joseph presumably was. Other prisoners,

however, were simply being held in prison awaiting the decision

of the government as to what their punishment was to be. In

other words, they were waiting to find out if they were going to

be executed. This last category seems to be that of the two

individuals Joseph met while in prison, the Butler and the

Baker.

Who

were the two individuals? We are never told their names or their

crimes. The fact that one of them, the Baker, was eventually

executed, and the other, the Butler, was restored to office,

leads us to believe that they were accused of being involved in

some kind of plot against the king. Such things happened in

ancient Egypt. In such a case, once the king sorted out the

facts, the guilty would be punished and the innocent would be

exonerated. The Baker was executed (for treason) and the Butler

was restored to his position. But what was that position?

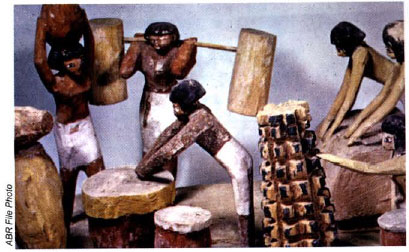

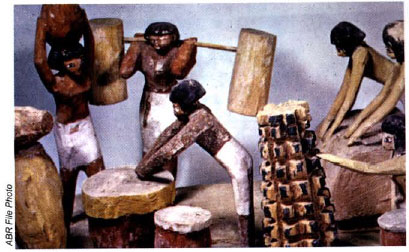

Tomb model of an ancient Egyptian bakery, Cairo Museum

We

get the term “butler” from the KJV translation of the Bible, and

it brings to our minds the very British concept of a man in a

tuxedo who answers doorbells and supervises household servants.

This does not reflect the situation in the Joseph story. The

Hebrew title is “Cup Bearer” (for a Middle Kingdom example, see

Vergote 1959:50). The duties of this personage involved

providing beverages to the king; hence we see the importance of

having someone trustworthy on the job.

Getting back to the prison itself, let us see what else the

Hayes papyrus tells us about it. The main prison was located at

Thebes (modern Luxor) in Upper Egypt, some 400 mi south of the

Nile delta and modern Cairo. Assuming Joseph was there and not

at some smaller prison (a correct assumption I believe since key

royal officials were imprisoned there too), we see that the

entire Joseph story cannot be confined to the delta area of the

Nile as some scholars would have us believe.

As

the Genesis account states, there was a “Warden” or “Overseer of

the Prison,” who was assisted by a large staff of clerks and

scribes. Record keeping at such an institution was as important

to the ancient Egyptians as it is in a modem prison. The actual

title Overseer of the Prison is not commonly found in Egyptian

inscriptions, but examples do exist from the Middle Kingdom, the

time of Joseph.

One

of the chief assistants to the Warden or Overseer was the

“Scribe of the Prison.” In Genesis 39:22 we are told that Joseph

was promoted to high office in the prison. Since Joseph was

literate, as we have seen from the fact that he served as

steward in the household of Potiphar, it seems probable that he

was promoted to Scribe of the Prison. As such, he would not only

have been the right-hand man of the Warden, but he also would

have been in charge of all the records of the institution.

No

matter how high in rank he became, Joseph naturally would have

valued his personal freedom more than a high office in the

prison. When he interpreted the dream of the Cup Bearer as

meaning that the Cup Bearer would be freed and restored to his

post, Joseph implored that individual to remember him when he

has the ear of Pharaoh. The Cup Bearer promises to do so, but

quickly forgets Joseph when he assumes his old position again.

It is only when Pharaoh himself dreams a dream that the Cup

Bearer remembers the young Hebrew who could, through the power

of God, interpret dreams. At that time, Joseph is called out of

prison.

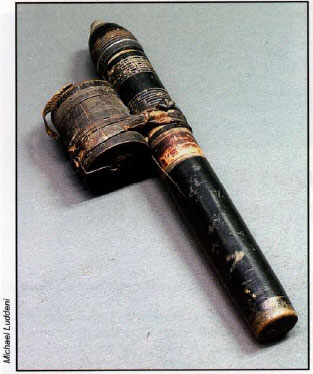

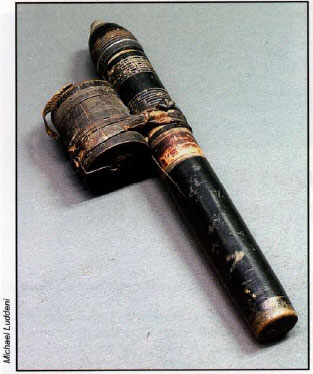

Scribe’s pen and ink set, Egyptian Museum, Berlin. Joseph would

have used a set such as this in his duties as steward and prison

official.

One

final point needs to be noted. Joseph, before going to the king,

has to change his clothing and shave (Gn 41:14). These are

significant details. Native Egyptians were very concerned about

personal cleanliness and the removal of all facial hair—the

beards worn by kings were false beards. If Joseph appeared

before a Hyksos, i.e. non-Egyptian Pharaoh, these factors would

not have been so significant. It is likely that the ancient

Hyksos were Amorites, and we have ancient pieces of art

indicating that the Amorites grew beards. This verse, therefore,

is further evidence that the Pharaoh of Joseph’s day was

Egyptian and not Hyksos, and that Joseph is correctly dated to

the Middle Kingdom period.

Pharaoh sent and called Joseph, and they brought him hastily out of the dungeon.

Pharaoh sent and called Joseph, and they brought him hastily out of the dungeon.

Tsiyon

Road on Glorystar Satellite!

Tsiyon

Road on Glorystar Satellite!