The mass murder, which provoked a volley of Egyptian air strikes on the group’s Libyan stronghold of Derna, realised long-held fears of militants reaching the Mediterranean coast.

The mass murder, which provoked a volley of Egyptian air strikes on the group’s Libyan stronghold of Derna, realised long-held fears of militants reaching the Mediterranean coast.

Isis started in Iraq and now controls swathes of adjoining Syria, including along the Turkish border, as part of its so-called Islamic State.

Its ideology has spread much further, with pledges of allegiance from terrorist groups in Egypt, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Yemen and now Libya.

Days before Isis released its gory video depicting the Egyptians’ beheadings, Libya’s former Prime Minister warned that the group would soon reach the Mediterranean and even Europe if order was not restored in the country.

Ali Zeidan said Libya’s fractured government and easy access to weapons seized during the fall of Colonel Gaddafi made it more susceptible to the activities of jihadists, according to The Times.

“(Isis) are growing. They are everywhere,” he added.

“In Libya, the situation is still under control. If we leave it one month or two months more I don’t think you can control it.

“It will be a big war in the country and it will be here in Europe as well.”

Libya has seen fierce fighting between rival militias since Gaddafi was overthrown during the 2011 Arab Spring.

Mr Zeidan, who fled to Europe after losing a parliamentary vote of confidence, reported that Isis had a growing presence in some of the bigger cities and was trying to recruit fighters from rival Islamist groups.

Aref Ali Nayed, Libya’s ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, also said Isis’s presence in Libya was increasing “exponentially”.

Aref Ali Nayed, Libya’s ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, also said Isis’s presence in Libya was increasing “exponentially”.

Its military gains last summer sparked a rush by other Islamist groups in the Middle East and North Africa to ally themselves with the group by pledging allegiance and changing their names.

The jihadists behind the beheadings in Libya call themselves the Tripoli Province of the Islamic State.

As the turmoil in Libya continued last year, they gained control of the port city of Derna and nearby Sirte, where Isis seized the murdered Coptic hostages in December and January.

As the turmoil in Libya continued last year, they gained control of the port city of Derna and nearby Sirte, where Isis seized the murdered Coptic hostages in December and January.

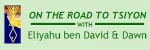

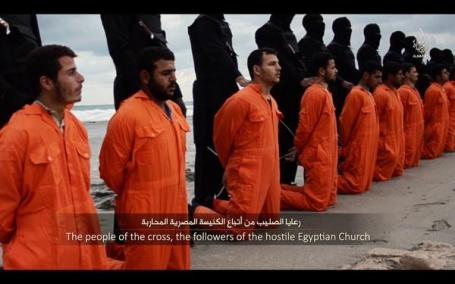

The location of their murders could not be confirmed but footage showed them dressed in orange jumpsuits kneeling on a beach. Behind each of them were masked militants who wielded their knives to kill the bound hostages simultaneously.

Isis affiliates have also claimed responsibility for attacks on the Egyptian military and police in the Sinai Peninsula, further along the Mediterranean coast between Egypt and Gaza.

***

The

Islamic War on Christianity

Reprint from: The Independent,

17 February, 2015

ISIS leads 21 Coptic Christians to their

beheadings on a beach in Libya

Almost fifteen hundred years ago, a wandering monk called John Moschos described the Eastern Mediterranean as a "flowering meadow" of Christianity. The religion had been born here nearly 600 years before but while, in the early years, it had been a persecuted, militant cult, under the patronage of the Byzantine emperors it had matured and mellowed. "The meadows in spring present a particularly delightful prospect," Moschos wrote in his book The Spiritual Meadow, which became a 7th-century best-seller. "One part of this meadow blushes with roses; in other places lilies predominate; in another violets blaze out…"

Christianity, in other words, was now flourishing right across

the region. No intolerant tyranny menaced it, no other religion

contested its right to grow and prosper and develop in different

ways. "The Eastern Mediterranean world was almost entirely

Christian" in Moschos's day, William Dalrymple wrote in his 1997

book From the Holy Mountain. "At a time when Christianity had

barely taken root in Britain… the Levant was the heartland of

Christianity and the centre of Christian civilisation… The

monasteries of Byzantium were fortresses whose libraries and

scriptoria preserved classical learning, philosophy and medicine

against the encroaching hordes of raiders and nomads [and] the

Levant was still the richest, most populous and highly educated

part of the Mediterranean world."

Today, the picture is dramatically different. Every corner of

the Middle East is locked in more or less violent struggle, but

whatever course the future takes, it is safe to predict that

Christians will play only a marginal part in it – if they survive

at all. Already, as the Prince of Wales recently pointed out, there

is a smaller proportion of Christians in the region than in any

other part of the world: just 4 per cent, and falling fast. Sunni

Muslim extremists see them not as "people of the Book" – members,

like Muslims, of one of the three great Abrahamic religions – but

as infidels, bracketed as the odious Other alongside Shias,

apostates, atheists, Baha'is.

For Muslim extremists, the Christian minority has become a

favoured target because they belong to the "wrong" religion; are

numerically few, weak and vulnerable; and are identified with the

oppressive policies of the Christian United States and Europe.

As Dr Khataza Gondwe, of Christian Solidarity Worldwide, told

me: "In Egypt and elsewhere, extreme Islamism portrays Christians

as a non-legitimate or foreign community that has no right to be

there – as a special interest group of the West. In Iraq, the

debate surrounding the invasion and war has distorted the issue

and, meanwhile, the Islamist extremists there have decimated one of

the oldest Christian populations in the world."

Battlefields of belief: Egyptian Coptic Christians visiting a church (Getty Images)

Battlefields of belief: Egyptian Coptic Christians visiting a church (Getty Images)

Some of the most shocking cases of religious persecution in

recent years have involved Muslims. Twelve years ago, in the Indian

state of Gujarat, nearly 800 Muslims died in riots orchestrated by

Hindu nationalist militants. In Burma, violence against Muslims

committed by Buddhists, including Buddhist monks, has erupted

repeatedly since the killing of a Buddhist girl in Arakan state in

June 2012, despite condemnation by the outside world.

But those ugly events are peculiar to the countries in which

they occurred. The attacks on Christians, by contrast, follow a

clear pattern from country to country. From Nigeria and Somalia via

Egypt, Syria and Iraq to Pakistan, Christians are being targeted

ever more frequently by Islamist extremists. A sample of atrocities

across these countries gives an idea of the rising tide of terror

from which Christians are suffering:

In Egypt, many supporters of deposed President Morsi

irrationally blamed Coptic Christians for his downfall, and took

revenge on them. They seized control of the remote town of Delga,

burning down three of the five churches there, and forced thousands

of Christians to flee. They looted the 1,600-year-old monastery of

the Virgin Mary and St Abraam and set fire to it. "They [the Copts]

alone were set up as scapegoats and erroneously blamed for

instigating the violent dispersal of pro-Morsi demonstrators,"

Bishop Angaelos, of the Coptic Orthodox Church in the UK, told a US

Congressional hearing.

In Syria, as jihadists gained the upper hand over more

moderate rebels, the village of Maaloula, where many still speak

ancient Aramaic, the language of the Bible, was invaded by rebels

who attacked churches, forcing many among the 3,000-strong

population to flee. Elsewhere in the country, two archbishops were

abducted by gunmen in April last year and have yet to reappear.

In Iraq on Christmas Day, 24 people were killed when a bomb

exploded outside a church in Doura, southern Baghdad, as

worshippers were leaving at the end of a service. Dozens more

Christians were killed elsewhere in the country during the

Christmas period. Prior to the Iraq war, there were 1.4 million

Christians in the country, around 3 per cent of the population.

Since then, the number has fallen to about 300,000. Raphael I Sako,

the Chaldean Patriarch of Baghdad, said: "If emigration continues,

God forbid, there will be no more Christians in the Middle East.

[The Church] will be no more than a distant memory."

In Pakistan, 85 Christians were killed when two suicide

bombers blew themselves up outside a historic church in the

frontier city of Peshawar in September 2013. Standing in the

church's courtyard and comforting the wounded, the Bishop Emeritus

of Peshawar, Mano Rumalshah, commented afterwards: "It's not safe

for Christians in this country. Everyone is ignoring the danger to

Christians in Muslim-majority countries. The European countries

don't give a damn about us."

Christian campaigners have long lamented the reluctance of

politicians or media in the West, and Europe in particular, to take

a stand against the growing wave of violence. Dr Gondwe remarks

that "sectarian attacks on Egyptian Copts have been occurring for

decades, but many people in the West have appeared reluctant to

speak out. For a time, it seemed as if journalists and human rights

organisations were anxious not to be seen as displaying a bias

towards Christianity."

But now, says Dr Gondwe, there has been "a complete turnaround.

In Nigeria, the brutality of the Islamist militia Boko Haram has

meant that people could not ignore the events on the ground. In

Egypt, Copts and young Muslims participated alongside each other in

the Tahrir Square protests, and members of the Muslim community

speak out strongly against sectarian violence. There are voices in

the Muslim community saying: 'We are Egyptians first'."

The aftermath of a suicide bomb attack on a Catholic church in Nigeria (Getty Images)

The aftermath of a suicide bomb attack on a Catholic church in Nigeria (Getty Images)

Meanwhile, the recent changes at the top of the Catholic and

Anglican churches have also made a difference, with Pope Francis

and Archbishop Welby focusing attention on persecuted Christians.

But it was Prince Charles who said the previously unsayable in a

blunt speech to religious leaders at Clarence House at Christmas.

"We cannot ignore the fact," he told them, that [Christian

communities in the Middle East] are increasingly being targeted by

fundamentalist Islamist militants." He went on to except Jordan

from the charge – "Jordan has set a wonderful example… [it] is a

most heartening and courageous witness to the fruitful tolerance

and respect between faith communities."

Yet the latest research – from Open Doors, a US organisation

that publishes annual figures for Christian persecution – shows

that jihadi violence is increasingly spilling over into Jordan from

the Syrian civil war, causing Jordan to jump up eight places in the

list of countries where Christians are most at risk of

persecution.

..Christians are being

deliberately killed in large numbers on account of their faith in

the region where it first flourished. When John Moschos was

gathering his "flowers" from the unmown meadow of Christianity in

the late 6th century, the Byzantine Empire was already in steep

decline, and it was not long before the followers of the Prophet

Mohammed finished it off. Yet, despite the loss of its imperial

protector, Christianity in the region has survived more than a

millennium of Muslim domination. Its congregations may have shrunk

and its culture stagnated, but it was permitted a place and a role

of its own both in the Ottoman Empire and in the nation states that

succeeded it.

The idea that Christians – those fellow People of the Book –

should be bombed and slaughtered and terrified into flight, their

churches and monasteries burned down and their history expunged:

these evil developments are quite new. The Nazis did their best to

wipe out all trace of Judaism in Europe. A similar effort – less

systematic and scientific, certainly – now menaces the survival of

Christianity where it was born. We are beginning to see this

disaster for what it is. But it may be too late to reverse it.

This

may surprise some readers, but I see this mass exodus of Christians and Jews

(including converted Muslims) from Muslim lands to be an answer to prayer, which

was called for in program #136 posted on our

Tsiyon.org website back in 2008 (See left). In that

program it was revealed that the pale horse rider of Revelation had been

released, and was already moving the Middle East Islamic countries toward a

catastrophic war in which untold numbers will be killed. Since then, events in

the Middle East have been tracking, as if by an unseen script, toward exactly

that fate. As we consider the multiple heinous crimes that radical Islam is

heaping up before YHWH, who can deny that such a punishment is not just? That

is, except for the righteous who live there. That's why, with that program, I

asked all listeners to begin praying for the righteous in the Islamic world to

escape, before the judgment falls. Today, in this newsletter, I feel the need to

renew that call. Friends, please, pray with me for all of the righteous now

dwelling in Islamic countries, that YHWH might quickly move them out of those

places, into places of safety for them, before catastrophic judgment falls upon

the jihadist enemies of YHWH. Make no mistake, this Islam-shattering war is

coming, and it will change everything, everywhere.

This

may surprise some readers, but I see this mass exodus of Christians and Jews

(including converted Muslims) from Muslim lands to be an answer to prayer, which

was called for in program #136 posted on our

Tsiyon.org website back in 2008 (See left). In that

program it was revealed that the pale horse rider of Revelation had been

released, and was already moving the Middle East Islamic countries toward a

catastrophic war in which untold numbers will be killed. Since then, events in

the Middle East have been tracking, as if by an unseen script, toward exactly

that fate. As we consider the multiple heinous crimes that radical Islam is

heaping up before YHWH, who can deny that such a punishment is not just? That

is, except for the righteous who live there. That's why, with that program, I

asked all listeners to begin praying for the righteous in the Islamic world to

escape, before the judgment falls. Today, in this newsletter, I feel the need to

renew that call. Friends, please, pray with me for all of the righteous now

dwelling in Islamic countries, that YHWH might quickly move them out of those

places, into places of safety for them, before catastrophic judgment falls upon

the jihadist enemies of YHWH. Make no mistake, this Islam-shattering war is

coming, and it will change everything, everywhere.

The mass murder, which provoked a volley of Egyptian air strikes on the group’s Libyan stronghold of Derna, realised long-held fears of militants reaching the Mediterranean coast.

The mass murder, which provoked a volley of Egyptian air strikes on the group’s Libyan stronghold of Derna, realised long-held fears of militants reaching the Mediterranean coast. Aref Ali Nayed, Libya’s ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, also said Isis’s presence in Libya was increasing “exponentially”.

Aref Ali Nayed, Libya’s ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, also said Isis’s presence in Libya was increasing “exponentially”. As the turmoil in Libya continued last year, they gained control of the port city of Derna and nearby Sirte, where Isis seized the murdered Coptic hostages in December and January.

As the turmoil in Libya continued last year, they gained control of the port city of Derna and nearby Sirte, where Isis seized the murdered Coptic hostages in December and January.